May 13-14, 2011, George Mason University

“Teaching the Middle East after the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions…Beyond Orientalism, Islamophobia, and Neoliberalism,” a conference sponsored by the Middle East Studies Program and the Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University, and by the Arab Studies Institute (which includes Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya), brought together forty participants for an intense two-day conversation regarding the future of pedagogy and scholarship dealing with the region (see List of Participants and Abstracts below).

The invited participants represented a wide range of disciplines and approaches, and the discussions brought together scholars whose work has been central to the development of the field with new voices whose work has emerged in recent years, in order to address the question: What sorts of teaching and research agendas do we need to establish in order to address the histories and emerging realities of the region? The ensuing conversations helped to lay the foundations for the ongoing work of elaborating, critiquing, and beginning to realize these pedagogical and scholarly agendas.

[Panel on "Reframing Research Agendas and Analytical Narratives. Left to right: Cemil Aydin, Pete Moore, James Gelvin, Zachary Lockman, Nadya Sbaiti, Rabab Abdulhadi, Hesham Sallam]

Given the timing of the conference in the midst of the still-ongoing Arab Spring, the events of recent months, including the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt and the continuing popular uprisings throughout the region, were front and center in these discussions. However, the deeper rationale behind the conference goes further back. The full raison d’etre for the conference was set out by Bassam Haddad during his opening remarks. As he noted, during the past decade, we have witnessed an important theoretical questioning of the dominant conceptual tools used to analyze the social, political, and cultural lives of Middle Eastern societies. The moment of the Arab Spring, taken together with this ongoing questioning process, presents itself, Haddad suggested, as a particular opportunity to switch pedagogic and scholarly modes and strategies from "defensive" to "non-defensive" ones across the board. Traditionally, many educators have found themselves forced to teach the Middle East in defensive ways that were consumed by reacting to dominant but reductionist world-views and paradigms, especially at the undergraduate level. A glance at the state of mainstream discourse regarding the region, whether in terms of media coverage or policymaking, reveals both the poverty and the power of these dominant paradigms; students, even those with an interest in the region, are of course deeply influenced by these paradigms before they ever reach the classroom. This fact has been exacerbated by the fact that specialists in the field of Middle East Studies who come from different disciplinary backgrounds have not always been able to find ways to speak across these disciplinary differences; the attempt to foster this conversation was, as Haddad noted, another of the important motivations behind the conference.

Some of the most important intellectual developments in the analysis of the region have emerged as ways of disputing and disrupting certain dominant narratives, including approaches founded in critiques of Orientalism, Islamophobia, and neoliberalism. These approaches continue to provide crucial tools, but as Haddad noted in his remarks, the opportunity to move away from defensive modes of reaction, and towards new sorts of non-defensive scholarly and pedagogical strategies, has begun to emerge. Needless to say, the recent revolts and revolutions in the region have sped up this process, and have opened the door for a fundamental rethinking of the methodologies and paradigms used to understand the Middle East. Empirically, we are witnessing a rare teachable moment, when so much of what many educators have been working to debunk in the classroom is being debunked before our eyes in the region. But, as Haddad pointed out, this does not mean that what we are seeing and experiencing is necessarily an automatic teachable moment; what we need, in other words, are pedagogical and research strategies designed to help seize the moment and work towards larger sorts of transformations in the teaching of the Middle East.

Meanwhile, even denizens of the mainstream media and of policymaking, who have traditionally been hostile to those voices that have challenged the dominant paradigms for thinking about the region, have begun to pay heed to some of these same voices to explain the popular uprisings of the Arab Spring — events which their usual stable of “experts,” steeped in the narratives of Orientalism, Islamophobia, and neoliberalism, had declared to be impossible. Indeed, one of the most important sets of discussions that emerged at the conference focused on the role of the intellectual in the wake of these developments, and where educators and scholars should best aim their voices today: Should the goal be to try to influence policymakers in Washington and other traditional centers of power? Should it be to try to intervene in and change the way the media covers the region? Should it be to find other ways to reach larger audiences, including students, in a way no longer focused on simply reacting to and countering the dominant narrative, but based instead on helping this larger audience to become aware of new modes of thinking about the region?

As the panel reports and abstracts show, these and other crucial questions were raised and addressed throughout the conference; the closing discussion sessions in turn added new questions that will be addressed in the ongoing work to come. Through the discussions, panelists moved productively between addressing current events (with frequent reminders both of the urgency of findings modes of analysis for these events, but also the humility necessary for doing justice to their evolving and fast-changing nature) and thinking through larger questions of methodology. Questions emerging from the ongoing popular uprisings — for example, whether the term “revolution” is an accurate one to describe what has happened in Tunisia and Egypt — sent participants back to issues of methodology, such as the question of how to formulate new modes of comparative study of revolutions. On the other hand, methodological questions, such as the tension between modes of analysis grounded in political economy and those related to discourse analysis, came to be considered and tested not as abstract disciplinary questions, but rather in terms of what they might help us to understand about recent events, and how they might provide useful frameworks for future inquiries.

[Presentation by Khalid Medani. Left to right: Linda Herrera, Toby Jones, Khalid Medani, Ziad Abu-Rish]

What follows are a series of summaries of the panels that made up the conference. The first six panels featured a series of presentations followed by a discussion period. The final two panels were designed entirely as discussions, meant both to provide a conclusion to the conference and also to set the agenda for the ongoing discussion that will follow; the first concluding panel focused on setting research agendas, and the second on setting agendas for pedagogical approaches and teaching strategies. Each panel summary includes links to comprehensive abstracts of each individual presentation; these abstracts can be found in the Pedagogy section of Jadaliyya.

One of the motivations behind this conference was the understanding that the attempt to switch modes from a defensive to a non-defensive approach, and the effort to develop new pedagogical and research agendas in order to address the events of the Arab Spring and beyond, will require institutional backing, networking, collaboration, and innovation. This conference was conceived in hopes of contributing to this goal, and the ongoing work that comes out of the discussions begun at the conference will proceed with this same goal in mind. The Jadaliyya Pedagogy page will be one place where this work will go forward, so we hope that you’ll all join us for the discussion there.

We at Jadaliyya, along with Arab Studies Journal, would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Ali Vurak Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies and the Middle East Program, both at George Mason University, without who`s financial and logistical support, the conference would not have been possible.

Click here for Panel Summaries of Day 1 of Jadaliyya`s "Teaching the Middle East" conference.

Click here for Panel Summaries of Day 2 of Jadaliyya`s "Teaching the Middle East" conference.

Click here for Conclusions of Jadaliyya`s "Teaching the Middle East" conference.

PARTICIPANTS AND ABSTRACT TITLES

Producing Knowledge for Justice? Gender and Sexuality Studies and the Consumption of Arabs and Muslims

Rabab Abdulhadi

College of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University

Regional Uprisings and Middle East Scholarship: Some Thoughts on What We Can Do Better

Ziad Abu-Rish

Department of History, University of California, Los Angeles

Teaching Arab Identity and Islam in Light of the Arab Uprisings

As’ad Abukhalil

Department of Politics & Public Administration, California State University Stanislaus

Pedagogical Uprisings: Teaching to the Unconverted, or Against Multiculturalism’s Middle East

Tony Alessandrini

Department of English, Kingsborough Community College- City University of New York

How the Egyptian Revolution Teaches Political Sociology, Global Political Economy, Gender Studies, and Geopolitics

Paul Amar

Global & International Studies Program, University of California, Santa Barbara

Rescuing History of Universalism and Modernity from Eurocentric Decline Paradigm

Cemil Aydin

Department of History and Art History, George Mason University

Who’s Afraid of Iran? Neocons’ Enduring Influence on US Policy Analysis

Shiva Balaghi

The Cogut Center for the Humanities, Brown University

Comparative and International Law of the Middle East After the Uprisings: Re-assessing the State of the Arab State

Asli Bali

School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles

Workers and Egypt’s January 25th Revolution: Shifting the Discussion from Autocracy/Democracy to Political Economy and Equity

Joel Beinin

Department of History, Stanford University

Teaching Political Islam after “Post-Islamism” and the Arab Revolutions

Michaelle Browers

Department of Political Science, Wake Forest University

How the January 25th Uprising Is Reshaping the Norms of Egyptian Domestic and Foreign Policy

Jason Brownlee

Department of Government, University of Texas at Austin

Problematics of Teaching International Law in the Contemporary Middle East

Noura Erakat

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University

Rethinking the Big Picture: Narrating Middle Eastern History in the Wake of the Arab Uprisings, 1944-Present

James Gelvin

Department of History, University of California, Los Angeles

Thoughts Out of Season

Peter Gran

Department of History, Temple University

Prospects for Shifting Strategies: The Production of Knowledge on the Middle East and in the Classroom

Bassam Haddad

Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University

Following the Torture Trail From Middle East Studies to American Studies

Lisa Hajjar

Department of Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Teaching Islam After the Revolution

Sumaiya Hamdani

Department of History and Art History, George Mason University

Youth and Citizenship in a Digital Age

Linda Herrera

Department of Educational Policy Studies, University of Illinois

Unlearning while Teaching on the Arab Media

Adel Iskandar

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University

Democracy and Its Limits in the Persian Gulf

Toby Jones

Department of History, Rutgers University

Muddles in the Models: Ethnography and the Mapping of the New Middle East

Laurie King

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University

Making Connections

Zachary Lockman

Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, New York University

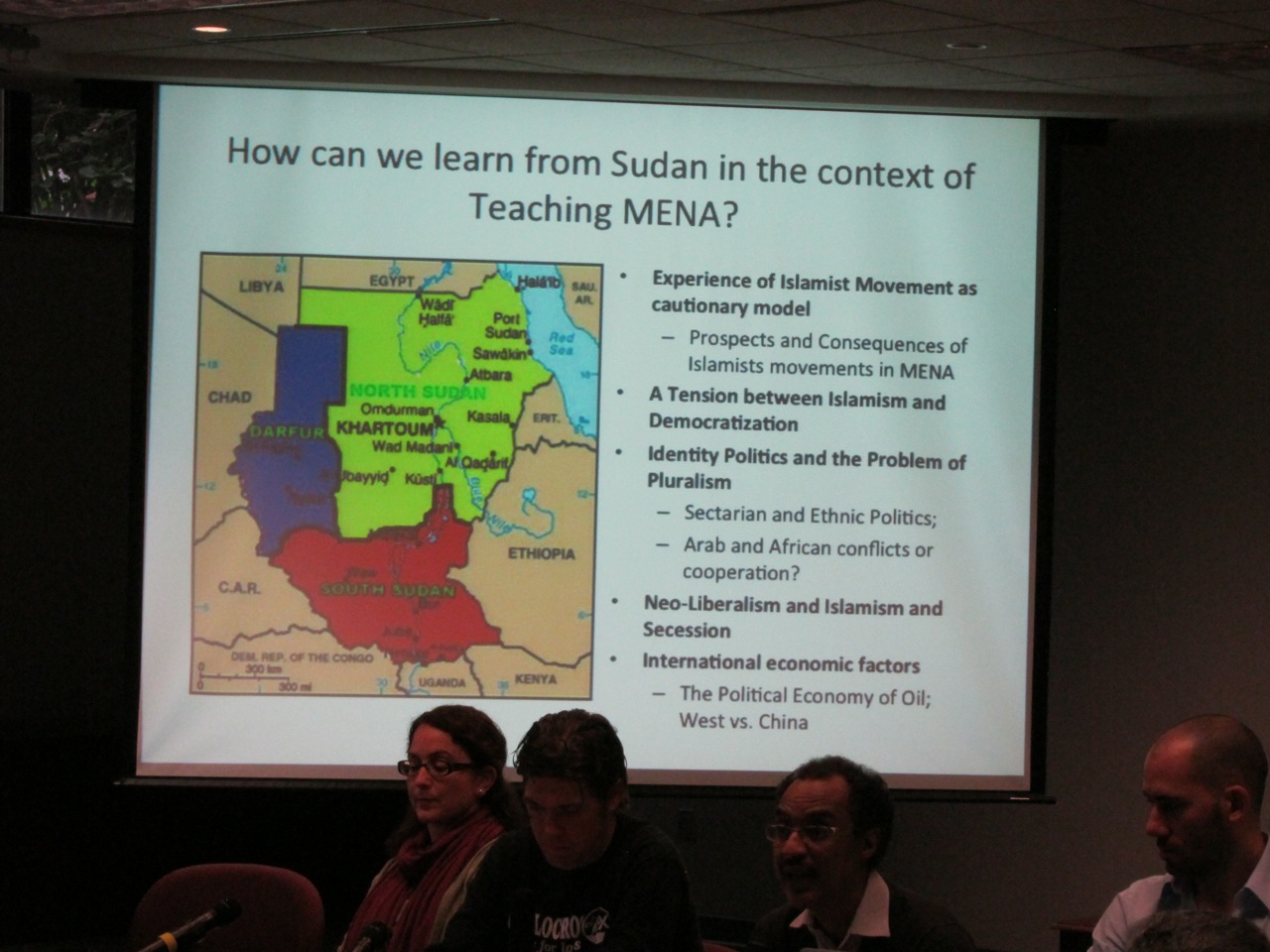

The Emergence of North and South Sudan: Reinterpreting the Politics of the Nile Valley in the Context of the Arab Revolutionary Movements

Khalid Medani

Department of Political Science, McGill University

Teaching the Middle East After the Revolutions: Critical Perspectives

Maya Mikdashi

Department of Anthropology, Colombia University

Back to Basics in Political Economy: Power and Inequality

Pete Moore

Department of Political Science, Case Western Reserve University

De-Orientalizing Pedagogy

Nadine Naber

Women’s Studies, University of Michigan

Teaching Middle East in Theory Courses

Agnieszka Paczynska

Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University

Challenges and Tradeoffs in Moving Beyond Dominant Approaches to the Study of the Comparative Politics of the Middle East

Hesham Sallam

Department of Government, Georgetown University

Disoriented: Rethinking Middle East, Far West, and the Points in Between

Nadya Sbaiti

Department of History, Smith College

Egyptian History Without “Egypt”? Privileging Pluralism in a Post-Revolution Pedagogy

Paul Sedra

Department of History, Simon Fraser University

The Social Relations of Islamophobia and the Role of the Academic

Stephen Sheehi

Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of South Carolina

Revolutions and Teaching the Middle East and Islam

Hayrettin Yücesoy

Department of History, Saint Louis University

NON-PRESENTING PARTICIPANTS

Osama Abi-Mershed

Department of History, Georgetown University

Amaney Jamal

Department of Politics, Princeton University

Darryl Li

Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University

Burhanettin Duran

Department of Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul Sehir University

Kadir Ustun

Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, Washington DC

Nuh Yilmaz

Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, Washington DC